|

This tune was composed by the Pipe Major John McLellan DCM (the acronym stands for "Distinguished Conduct Medal" - the second-highest military decoration (after the Victoria Cross) for spectacular action). He won the award for his courageous conduct during the battle of Magersfontein (*), where he rallied the troops at the sound of his pipes while he was seriously wounded at the ankle. In memory of this moment, which inspired him, he later wrote Lochanside. Known to pipers as “John McLellan, Dunoon” but to friends and family as “Jock,” John McLellan was a quiet and shy man who composed some of the most enduring melodies in pipe music. He was born in Dunoon on August 8, 1875. He had two brothers and three sisters. His father died of pneumonia when John was just 8, leaving his 41-year-old washerwoman mother to raise the family, the youngest of which was just a year old. Little is known about his early piping life, or even who taught him. This was perhaps partly because he was known to be modest to a fault and would very rarely talk about himself. Very few photos of him have come to light. |

|

Besides being a piper, he played the fiddle and was said to be an excellent whistle player. He was a middling painter and poet, and one of the few composers who often wrote lyrics to his tunes. In some cases he wrote the lyrics first. He was known to write light verse at the front, 100 yards from the German lines, and his poetry was often published in newspapers in the west of Scotland.

He died at 73 on July 31, 1949 at Dunoon Cottage Hospital of colon cancer and was buried with full military honours in Dunoon Cemetery. He was listed as single, and had no children.Among his greatest contributions are The Highland Brigade at Magersfontein, Heroes of Vittoria, The Bloody Fields of Flanders and The Dream Valley of Glendaruel, The Cowal Gathering, or The Road to the Isles. But Lochanside remains his magnum opus. It differs from other similar songs by its pace considered by many as wonderfully unusual. It is at the same time a march, a retreat or a festive tune. Played both in solo or massed bands, it is now present in most of the pipes bands’ tunes book.

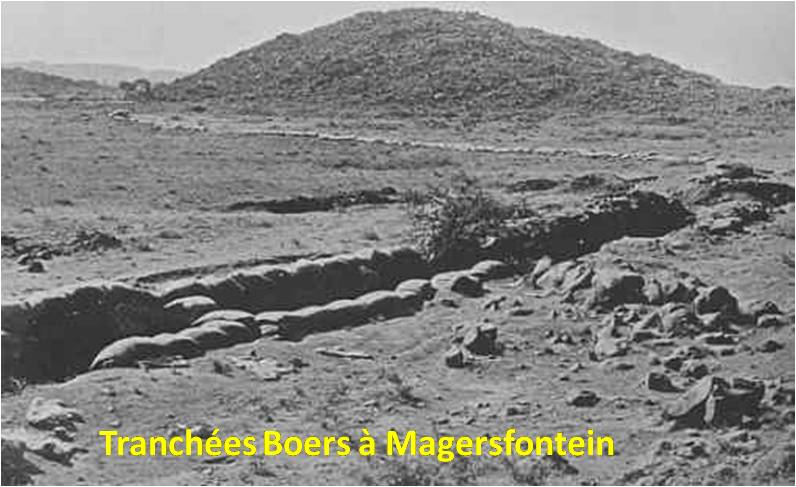

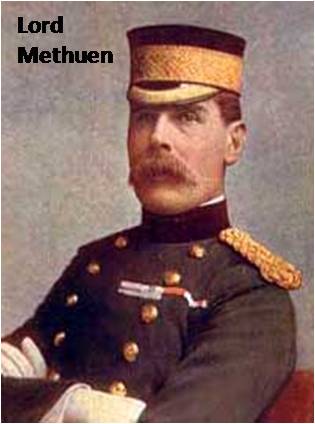

(*) The Battle of Magersfontein was held on December 11, 1899 near Kimberley 6 miles north-east of the Modder River, Africa South. It opposed the Boer army commanded by Piet Cronje and De la Rey, who defeated the English forces commanded by Lord Methuen.

The Boer War was a serious jolt for the British Army. At the outbreak of the war British tactics were appropriate for the use of single shot firearms, fired in volleys controlled by company and battalion officers; the troops fighting in close order. The need for tight formations had been emphasised time and again in colonial fighting. In the Zulu and Sudan Wars overwhelming enemy numbers armed principally with stabbing weapons were easily kept at a distance by such tactics. These tactics had to be entirely rethought in battle against the Boers armed with modern weapons.

The commandoes, without formal discipline, welded into a fighting force through a strong sense of community and dislike for the British. They had a perfect knowledge of the field and mounted infantry was able to shoot the rifle while galloping. Highly mobile and invisible, fighting without adopting formal training of battle they seemed elusive for the British troops remained in the patterns of the Crimean and India and incapable of winning battles against entrenched troops armed with modern magazine rifles. Consistently outnumbered the Boers were forced to a defensive war, but adopted tactics prefigured those that would be used later during the First World War.

|

The British regiments made an uncertain change into khaki uniforms in the years preceding the Boer War,

with the topee helmet as tropical headgear. Highland regiments in Natal devised aprons to conceal

coloured kilts and sporrans. By the end of the war the uniform of choice was a slouch hat, drab tunic

and trousers; the danger of shiny buttons and too ostentatious emblems of rank emphasised

in several engagements with disproportionately high officer casualties.

The British infantry were armed with the Lee Metford magazine rifle firing 10 rounds. But no training regime had been established to take advantage of the accuracy and speed of fire of the weapon. Personal skills such as scouting and field craft were little taught. The idea of fire and movement was unknown, many regiments still going into action in close order. The British regular troops lacked imagination and resource. Routine procedures such as effective scouting and camp protection were often neglected.Some of the most successful British troops were the non-regular regiments; the South Africans, Canadians, Australians and New Zealanders, who more easily broke from the habit of traditional European warfare, using their horses for transport rather than the charge, advancing by fire and manoeuvre in loose formations and making use of cover, rather than the formal advance into a storm of Mauser bullets. The war was followed by a complete re-organisation of the British Army. |

|

Magersfontein battle

Following Lord Methuen’s hard won victory at Modder River on 28th November 1898, the British paused to rebuild the railway bridge, broken down by the Boers; a precaution essential in Methuen’s view to enable him to relieve Kimberley, the main place for diamonds’ production.|

Although forced back from the Modder River position, the battle justified De la Rey’s tactic of

entrenching his riflemen on level ground, rather than on the top of hills, where they were vulnerable

to fire from the powerful British artillery.

The British delay at Modder River bridge enabled De la Rey to dig a further line of trenches at the base of Magersfontein Hill, 6 miles to the North East |

|

To carry out his task of relieving Kimberley, Methuen was bound to make the single strand of railway leading north to the town the axis of his advance; giving the Boers no difficulty predicting the British line of approach. Methuen made it easier still for De la Rey by announcing the imminent attack during the afternoon of 10th December 1899 with an extensive bombardment by his field artillery; completely ineffectual because, as usual, only led to the hilltops where the English thought their opponents entrenched to better spy on them, to dominate and take advantage of the slope at the assault.

|

|

|

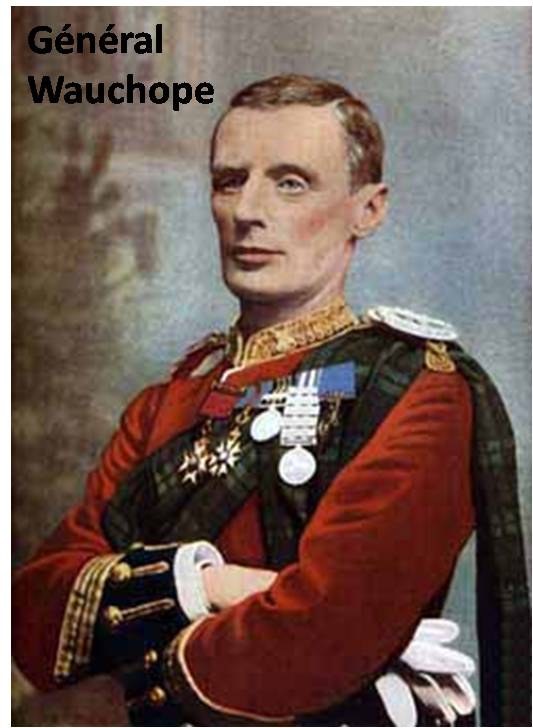

During the night the Highland Brigade under Major General Wauchope, comprising the 2nd Black Watch, 1st Highland Light Infantry, 2nd Seaforth Highlanders and 1st Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, made its approach march in close order, guided by the brigade major, Major Benson, to deliver a dawn assault on Magersfontein Hill. Daylight was breaking as the brigade approached the hill. At 1,000 yards from the Boers’ concealed entrenchments, Major Benson urged Wauchope that the brigade should move into open order, but the brigade commander, fearing that the soldiers would become disordered in the near darkness, continued the advance in close columns. When the order was finally given to move into open order the Boers opened fire. Wauchope was killed by the first volley of bullets. Thrown into confusion by the surprise attack the Highland battalions believed to find their salvation in rushing to the charge but their momentum was broken by unexpected barbed wire, an idea of Boer farmers who prefigured what will be trench warfare in 14-18. The Highlanders were unable to move forward or backward, and rushed to ground behind whatever cover they could find. The sun came up, revealing the Highlander Brigade pinned to the ground in front of the Boer positions. Whenever a soldier moved he attracted fire. They stayed there for the rest of the day also tormented by thirst and overwhelmed by the swarming ants.

We better understand why, drawing the battle in which he participated to write Lochanside, MacClellan has found this so special pace: cannot neither move forward, nor retreat and need reassurance on the spot... melody expresses both of all at once to share us soldiers’ dilemma and needs under fire.

Watching, almost powerless to intervene, Methuen sent forward companies of the 1st Gordon Highlanders to support their fellow Highland regiments and moved the Guards Brigade up on their right to engage the Boer left. The Boers had left a substantial gap between the Magersfontein positions and the trenches leading down to the river. There was an opportunity here, but Methuen did not attempt to take advantage of the gap after a heroic and incredible defence of a volunteer corps of 70 men struggling Scandinavian side of the Boers. They inflict on their opponents 10 times more losses than they have themselves before the Boers moved reinforcements in to cover between the two entrenchments.After nine hours exposed to constant fire in front of the Boer positions the highland regiments finally broke up and withdrew, suffering substantial losses as they rose from whatever cover they had found and made for the rear. The battle was over and Methuen had been soundly beaten. The British casualties were 902 men (53 officers) and Boer 236.

Magersfontein, Stormberg and Colenso were the defeats that made up “Black Week”. The losses in the Highland Brigade caused great distress in Scotland. Major General Andy Wauchope was something of a Scottish celebrity, having stood against Gladstone in the contest for the seat of Midlothian during the 1892 General Election, reducing the Prime Minister’s majority to 690. He is said to have been greatly mourned. This defeat caused Methuen to be side-lined. Lord Roberts and Lord Kitchener, on their arrival with further reinforcements, took over the advance in the West, leading to the inexorable invasion and conquest of first the Orange Free State and then the Transvaal and the relief of Kimberley and Mafeking.

Although there were more failures for the British, Lord Roberts in the West and General Buller in Natal pushed the Boers back, relieving Kimberley, Mafeking and Ladysmith, capturing the capitals of the Free State, Bloemfontein and the Transvaal, Pretoria and finally after a protracted guerilla campaign bringing the war to a successful conclusion.

This version is from Jim Malcolm.

Come the winter, cold and dreary Brings a hawk doon frae the high scree Tae the whin where snowy hares hide A aroond the Lochanside.

Come the spring the land lies weary

If ye’d been ye’d have seen the scatter

And the heron he comes a-creeping

Aye if you ever hae a reason

Summer time - the fish are louping

By the autumn the pinks are winging

If ye’d been ye’d have seen the scatter

And the heron he comes a-creeping

Aye if you ever hae a reason

Aye if you ever hae a notion

|

Quant arrive l’hiver, froid et triste Du haut des éboulis montagneux l’aigle plonge Vers les ajoncs enneigés où se cachent les lièvres Tout autour de Lochanside.

Quant arrive le printemps la terre est fatiguée

Si vous aviez été là, vous auriez vu se disperser

Et le héron avançant comme s’il rampait

Oui, si jamais vous aviez une raison

L’été venu – les poisons tourbillonnent

A l’automne les roses s’envolent

Si vous aviez été là, vous auriez vu se disperser

Et le héron avançant comme s’il rampait

Oui, si jamais vous aviez une raison

Oui, si tu veux avoir une idée

|

|

Lochanside - Small pipe

|